Until recently, I had only ever encountered oysters on the a la carte section of eloquent restaurant menus I couldn’t afford to dine at, and had never considered them to be an organism of any huge importance. However, after getting up close and personal with the native oysters and seeing them in their natural setting, my view completely changed.

During the summer of 2023, I spent a month working with Seawilding, a leading marine conservation charity in my home country of Scotland. I was eager to get some more hands-on experience working in the marine environment, and after a crazy few months of diving and travelling, wanted to contribute to the marine restoration work going on closer to home.

Community involvement is a key part of successful conservation projects. Seawilding is leading the way through inclusive conservation, such as volunteer days involving seagrass harvesting and sorting for planting in the loch. Photo credit: Philip Price, Seawilding

The month was humbling, challenging, exciting and rewarding all at once. I lived in a rustic little cottage on a farm, with another intern who is now one of my closest friends. On paper, it sounds like a dream, and it many ways it was. Every day was spent in the water, salt in our hair and the fresh ocean breeze in our lungs. We snorkeled almost daily in the seagrass meadows, harvesting seeds amongst the red feather stars and spiny starfish, and planted rhizomes to restore more seagrass habitat. We took the rib out to the offshore oyster nursery, and spent hours cleaning the cages and sorting through the oysters to individually assess their health and growth. Some days we collected data, running transect lines and video surveys, and analysing the biodiversity in each habitat. Other days we built oyster cages and carried them to the seabed, sampled water chemistry and did wildlife surveys along the shorelines.

Snorkelling through a Scottish seagrass meadow is a magical experience - teeming with life, these ecosystems provide huge ecological and environmental benefits to coastlines. Video Credit: Philip Price, Seawilding.

I remember back-rolling off the boat for the first time, and feeling like I had just fallen into a scene from avatar. Dappled sunlight filtered across meadows of seagrass, catching the flicking tails of goldsinny wrasse and dancing prawns. Long fronds of sea lace tangled round my legs as shore crabs wrestled and sparred across the seabed. Snakelock anemones blossomed like flowers as peacock worms waved and danced in the current, and I strained my eyes searching, hoping for a seahorse.

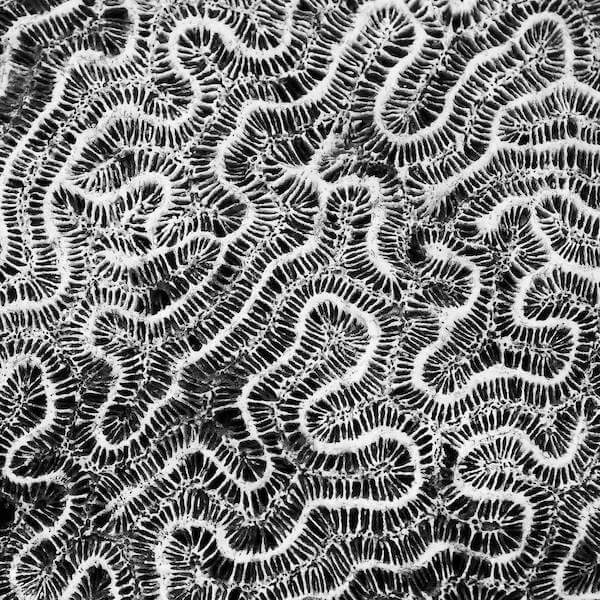

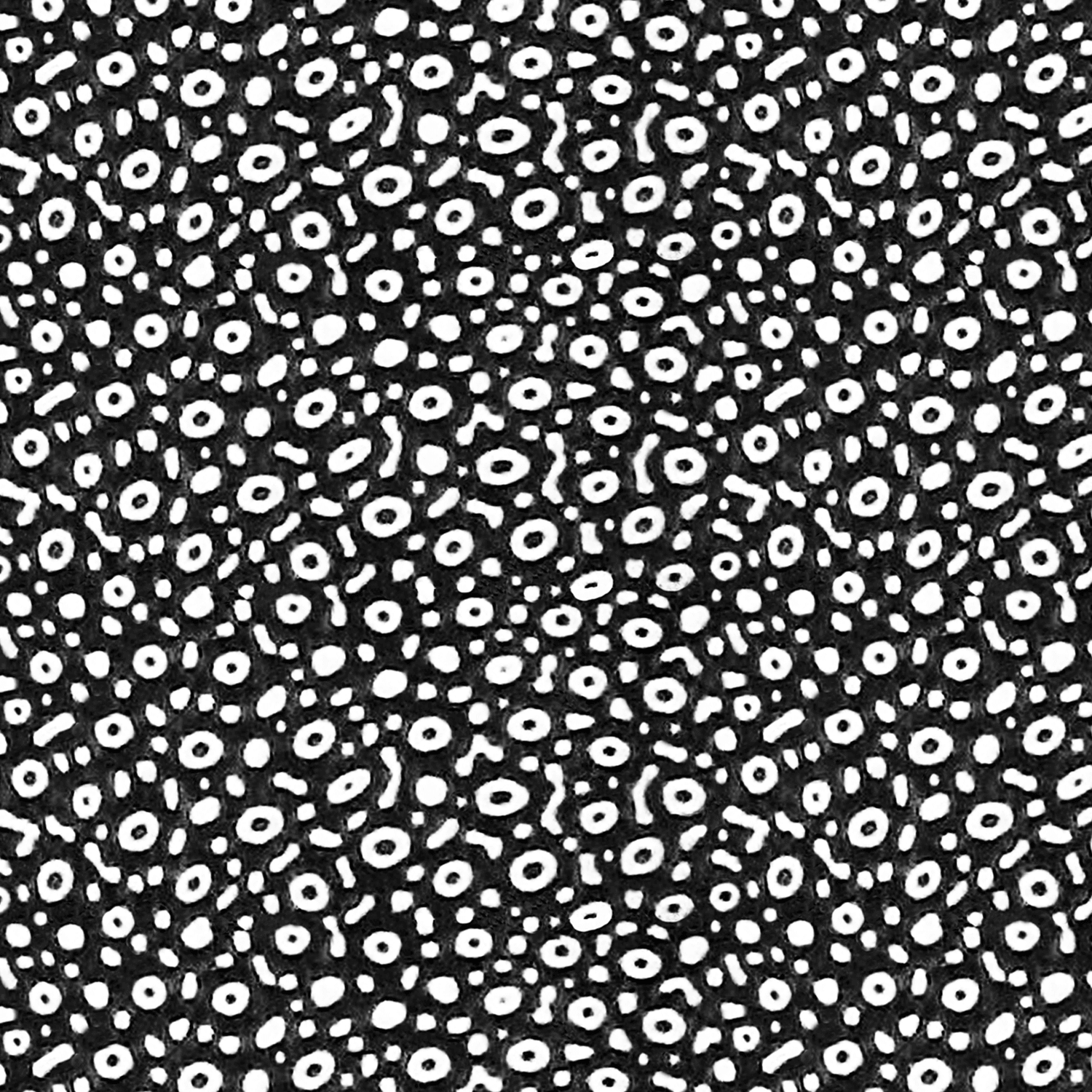

Beyond the fringes of the seagrass meadows, soft mudflats teeming with flatfish and sand gobies gave way to a cobble of oyster shells, stacked and layered into a living reef. Thick algae mats carpeted the seabed, with clumps of bladderwrack housing tiny fish which stared inquisitively as I passed. Folds of kelp hid treasure troves of shells; blue mussels, scallops, topshells, and I imagined octopus and catfish lurking in the swirling ink of the shadows. There could be anything in there – a basking shark had even been sighted in the loch the week before!

Living in a wetsuit, in and out of the sea all day, made me reach a level of happiness and satisfaction I didn’t know I could feel; I was learning about native ecosystems, contributing to conservation and having a blast at the same time. It was in no way effortless, but it was easy to love, especially with a good dose of banter with the team. There were so many little details that really made it magic; picking blackberries from the bushes for our morning porridge, watching gannets plunge and dive into the glassy waters, climbing the headlands to watch sunsets glow like embers over the sea, or spying the sleek and shiny outline of an otter slip into the water to catch its dinner. A highlight was making daily visits to the village café for warm, milky lattes after emerging from the sea in a state of near-hypothermia. Sure, it was August, but it’s Scotland. It’s just naturally cold.

The village of Ardfern is nestled on the gleaming shores of Loch Craignish, the sea loch where Seawilding's oyster and seagrass restoration is based. The passion and dedication to marine conservation of the Ardfern community is what drives Seawilding's success in its restoration projects. Photo credit: Philip Price, Seawilding.

I am glad I contributed to the work Seawilding is doing. Over a third of the UK’s natural seagrass beds have been lost in the past 50 years, and there are no natural oyster reefs remaining – thanks to dredging, overfishing and pollution. This has hugely degraded our shallow marine ecosystem health, as habitat has been lost, coastlines are exposed to erosion, less carbon is being stored and less water being filtered. Restoring and rejuvenating these habitats to their former health is an urgent task – and Seawilding is leading the way. Restoration will provide habitat and nursery grounds for a plethora of marine species, which creates a ripple effect up the food chain, helping feed many other species, as well as us humans through local fisheries. Oyster reefs are core water-filters, purifying the water through feeding so that it is crystal clear and optimal for seagrass to photosynthesise, which increases carbon sequestration. Both habitats act as buffers against harsh weather, cushioning the impact of storms and protecting the coastline in the face of climate change. We need these habitats to keep everything together. They are the bread and butter of our coastline.

Working with Seawilding was a life-changing experience; not just in the knowledge and expertise I gained, but also in the lasting friendships I made and the deep passion and love for the local wildlife that it cultured inside of me. Spending everyday underwater, I felt part of that oceanic world for a small snatch of time, and really got to know the patterns and quirks of the ecosystem, which are what really got me hooked. It’s a whole other world down there.

Seawilding is currently testing different methods of rhizome planting, to find the most efficient and successful method which can then be taught to other communities. Tried and tested methods include planting rhizomes in cardboard, hessian sacks, and human hair mats - all sustainably sourced! Video credit: Philip Price, Seawilding.

Without this close contact and in-depth research of oysters, and the crucial role they play in Scotland’s shallow marine ecosystem, I would be ignorant to the challenges facing this species – I would barely know what one looked like. Becoming familiar, and attached, to the oyster reefs of Loch Craignish in all their fishy, murky glory, made me realize how important it is that we share our knowledge and experiences of wildlife and natural systems.

When you learn about something, and begin to understand it, you naturally form an emotional attachment to it – and this is where passion is planted. Without passion for the environment, achieving conservation goals is tough; people protect the things they love, and this is the driving force behind the restoration projects across Scotland and globally, which are leading the ‘rewilding’ efforts the Earth so desperately needs.

The rich history, barren present, and uncertain future of oysters in the Scottish seascape is a prime example of how nature can be so easily commodified, and its inherent value cast aside. Oysters were exploited to the point of local extinction, deeming them a delicacy through their scarcity.

From above the surface, the vibrant biodiversity Loch Craignish hosts often goes unnoticed; the loch is thriving with life from mudflats studded with mosaics of shellfish to seagrass meadows harbouring shoals of all kinds of fish, often thousands strong.

My final take-home from my summer spent in the seas of the Scottish west coast, is that I love my country, I love its wildlife, and I want to do whatever I can to protect and conserve it. Through sharing knowledge and experience, support for conservation can grow and real change can happen. The more we talk about marine conservation, and what these habitats, species, and ecosystems mean to us, the more weight we can put on these issues, pushing us over the tipping point for creating a more optimistic future.

Oysters are no longer an option scrawled in curled font in the entrée section of a menu; they symbolize a movement of local communities, who are not waiting for governments to tackle climate change and marine conservation, but are taking action themselves. Oysters represent hope for Scotland’s marine ecosystem, public power in restoration, and show that the tide can be turned on a rocky history.

Sophie is in her final year studying BSc Ecological & Environmental Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. As an eager scuba diver, snorkeller, and ocean-lover, she has experience on the front lines of marine conservation, such as restoring coral reefs in Indonesia and sea grass in her home country of Scotland. She uses writing as a way to intertwine science and emotion, conveying the importance of marine ecosystems and raising awareness of current science, issues and news.

Ceila

February 27, 2024

What a wonderful way to support marine health. This was a great read. I would love to volunteer for seagrass restoration. I hope waterlust will debut a seagrass conservation line!